Time can often be our most precious resource. That's particularly true when it comes to retirement planning and saving, where compound earnings and interest are essential to building one's nest egg.

Most people plan to fund their retirement through a combination of Social Security benefits, traditional and Roth retirement savings, and taxable accounts. And people often start retirement and claim their Social Security benefits when they reach full retirement age. For those born 1960 or later, their full retirement age is 67.

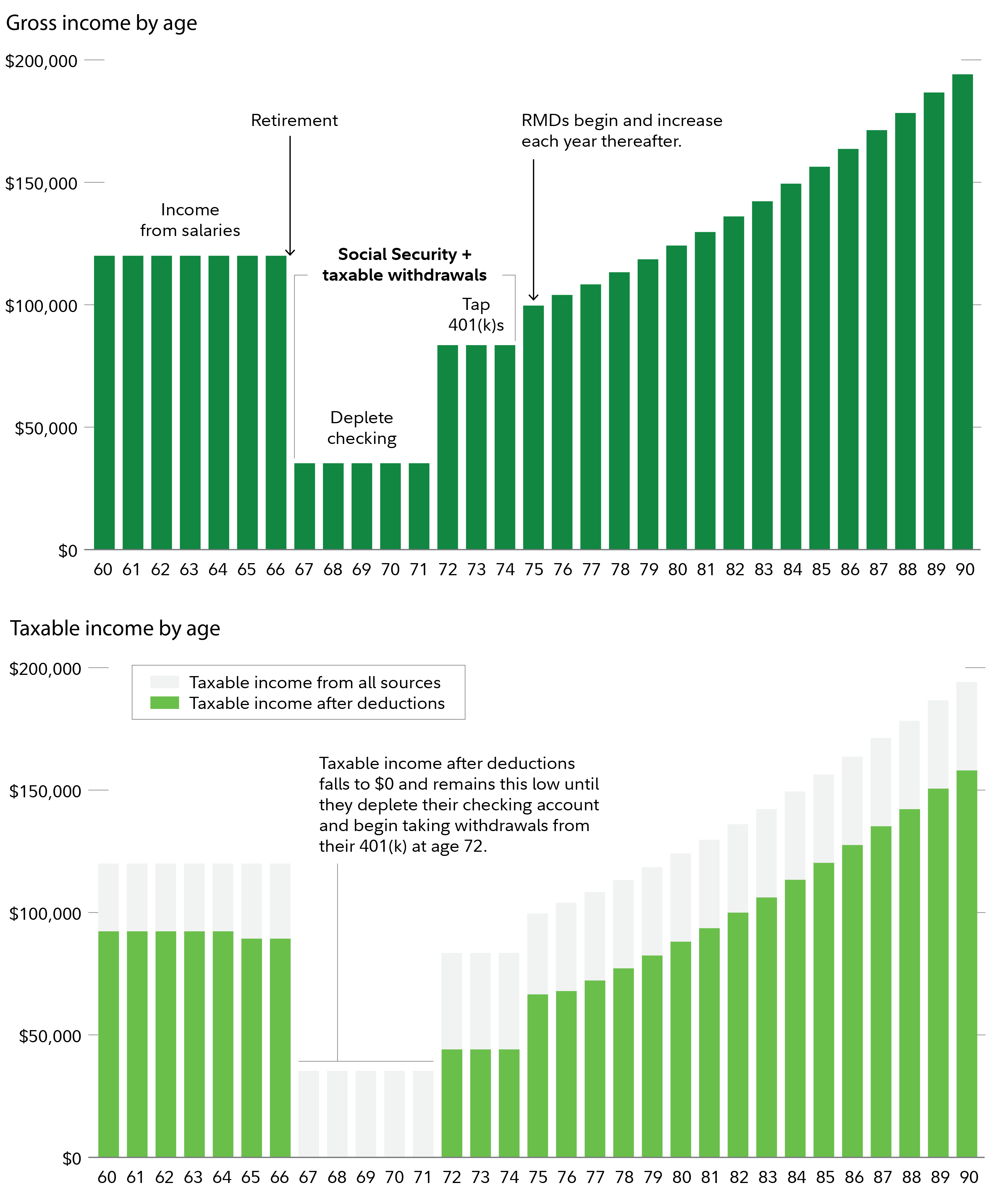

Until recently, required minimum distributions (RMDs) commenced when retirees turned 72, requiring withdrawals from tax-deferred accounts like 401(k)s and IRAs, which in turn resulted in higher income. For someone retiring at age 67, however, this created a 5-year period known as the "income valley" during which income and associated taxable income might be lower, potentially resulting in lower tax rates.

“Further, for those who didn't need to withdraw from their tax-deferred accounts during that period, taxable income in the income valley could drop as low as $0 due to the varying tax treatment of different income sources,” says Andrew Bachman, director of tax and retirement income for Fidelity’s Financial Solutions Team.

Thanks to the SECURE 2.0 Act, the income valley has increased, and these same retirees will have even more time to implement these tax strategies. As of 2023, the required beginning date (RBD) for RMDs increased to 73 for those people who haven't turned 72 in prior years. Beginning in 2033, the RBD jumps to 75 for people born in 1960 or later. And while that's many years away, the later RBD may apply to you and may extend the number of years you experience an income valley.

The income valley can be a good time to put a tax plan in place, because once you're out of the valley taxes on your ordinary income may increase again and RMDs may push you into a higher marginal tax bracket.

Why does the income valley exist?

The following is a hypothetical example of a couple named Sally and Carl with both taxable and tax-deferred assets entering retirement. It shows how they can fund their lifestyle, as well as some strategies they can implement during the income valley that could result in smoother (and potentially lower) tax bills during the income valley and throughout the rest of retirement.

The scenario is constructed in such a way as to make the point we often make, which is that as you are living in retirement, the different types of accounts you have may allow you to make strategic withdrawal decisions that ultimately influence how you realize taxable income. Therefore, there may be an opportunity to reduce tax liability in retirement. Individual circumstances will indicate to what extent this may be possible.

Let's assume the hypothetical Sally and Carl have a combined preretirement income of $150,000. In retirement, Sally and Carl expect to have expenses of $95,000. The difference between their combined preretirement income and their expenses can be the result of many factors, including saving on commuting costs, no longer needing to save for retirement, and potential tax savings due to different types of income between working years and retirement.

Understanding the income valley

In this hypothetical example, Sally and Carl are age 60 today and plan to retire at age 67. Among their considerations would be determining what resources they would have to live on during the income valley, and whether those will come from Social Security, a 401(k), taxable accounts, or a combination of all three.

How far the income valley dips depends on how they manage their account withdrawals. For example, withdrawals from a checking account are not considered gross income by the IRS and would not have an impact on taxes.

They experience an income valley while they live off their checking account and begin to take withdrawals from their retirement savings. Once the checking account is exhausted, they can withdraw only the portion they need to meet expenses from the 401(k) prior to RMDs beginning. In later years, the income valley ends when RMDs begin.

Next, we calculate Sally and Carl's tax situation each year. The table below uses the inflation-adjusted standard deduction of $30,000 for 2025 and additional standard deduction amounts of $1,500 each due to Sally and Carl since they are over age 65, plus $45,000 in annual Social Security benefits and $50,000 in taxable account withdrawals.1

Their taxable income falls to $0 and remains this low until they deplete their checking account and begin taking withdrawals from a 401(k) at age 72. Subsequently, when RMDs begin at 75, Sally and Carl's taxable income will rise as they are required to take distributions from the 401(k), which get larger over time. Their tax bills would grow as well, with occasional jumps as their income enters the next marginal bracket.

Making use of the income valley

The income valley years can create a valuable opportunity for tax planning. Here are 3 strategies to potentially consider using during those years, which might help reduce overall taxes or smooth taxes for some retirees.

1. Tax-savvy withdrawals

A tax-efficient withdrawal strategy once you're in retirement can help lighten your tax burden. One approach involves withdrawing first from taxable accounts—such as a non-interest-bearing checking account or brokerage account, then tax-deferred accounts, and finally with tax-free withdrawals from Roth accounts. While brokerage accounts may incur capital gains, long-term capital gains are taxed at 0% up to $96,700 of taxable income for a couple filing jointly and $48,350 of taxable income for a single filer for tax-year 2025.

Another approach is to make proportional withdrawals from each retirement savings account. Once a target amount is determined, you'd make withdrawals from each account based on the account's percentage of total savings. The overall effect could lead to more stable income as well as a more stable tax bill over time, by accelerating tax-deferred withdrawals and reducing future RMDs.

Additionally, proportional withdrawals could potentially lower lifetime taxes and potentially increase after-tax income by taking tax-deferred withdrawals during periods of low tax rates.

Keep in mind, however, that accelerating tax-deferred withdrawals from tax-deferred accounts may add to your ordinary income, which in turn could increase taxes on Social Security income, and potentially higher monthly payments for Medicare due to the Income-Related Monthly Adjustment Amount, or IRMAA. Consult a tax advisor to determine what makes sense for you.

Read more about Tax-savvy withdrawals in retirement in Viewpoints.

You can also gauge the potential effect of retirement income strategies on your taxes with Fidelity's retirement strategies tax estimator.

2. Consider a Roth conversion

If you have more resources, it may make sense to pay taxes on Roth conversions when your tax rate is low or even 0%, and after that you won't have to take RMDs from your account once it's converted. Additionally, qualified withdrawals from a Roth account in retirement are tax-free, assuming the 5-year aging rule has been met. A Roth IRA conversion will also decrease the amount of money in your tax-deferred accounts, meaning when you do start taking your RMDs from your tax-deferred accounts, your distribution amounts and taxes may also be lower. Similar to the tax-savvy withdrawals strategy, Roth conversions may also add to your ordinary income, which in turn could increase taxes on Social Security income. They could also lead to potentially higher monthly payments for Medicare premiums due to the IRMAA.

Read more about Roth IRA conversions in Viewpoints: Why consider a Roth conversion now?

3. Charitable giving may help

If you don't need the money, and you're feeling charitably minded, consider making charitable donations. For those who itemize or for whom a charitable donation would make itemizing more advantageous, a charitable donation can deepen the income valley by expanding the amount of income that is not taxed.2 This could mean more opportunity for the strategies mentioned above, or simply help reduce taxes during the income valley years.

Clients with more means could also consider a qualified charitable distribution (QCD). It's a direct transfer of funds from your IRA custodian, payable to a qualified charity. You can do a QCD of any amount, with a maximum of $108,000 per individual per year in 2025. QCDs are especially valuable once required minimum distributions (RMDs) begin if you don't need the full RMD for expenses. Note: Itemization is not required to make a QCD. The QCD amount is not taxed and counts toward your RMD. But you may not double dip and then claim the distribution as a charitable tax deduction. You must be age 70½ or older to donate a QCD.

For a deeper dive on charitable giving explore Viewpoints: Strategic giving: Think beyond cash.

Limitations

Of course, not everyone may have sufficient flexibility to manage their retirement income in the most tax-efficient way by choosing from taxable, tax-deferred, and tax-free accounts. Some people may only have tax-deferred assets to withdraw from, such as a 401(k) or an IRA, in which case they will have little choice other than to generate taxable income, or live on a lower amount of income. Others may have more flexibility; for example, a taxable checking or savings account. The change in income from preretirement to retirement can be huge for many, and the key to taking advantage of the "income valley" is flexibility.

Also, your other income sources—like Social Security, pensions, annuities, and rental income—may reduce the need for withdrawals in the first place, but they may increase your income and limit your flexibility to manage taxable income through strategic withdrawals. "That's because you can control how you take withdrawals, but you can't control how your overall income is taxed," Bachman says.

Finally, SECURE 2.0 expanded opportunities for retirement saving, including increasing the age at which required minimum distributions begin. Make sure to speak with your financial advisor or tax professional to understand how these changes might affect you—and how to make the most of the retirement income valley.