Converting money in a pre-tax (or traditional) 401(k) or IRA to a Roth 401(k) or Roth IRA has long had many potential advantages. Of course, you need to pay taxes on the converted amount. But once the money is in a Roth 401(k) or Roth IRA, you don't pay taxes on qualified withdrawals, giving you more flexibility to manage your taxes in retirement and boost after-tax income.3 While Roth IRAs have never had required minimum distributions (RMDs) during the owner's lifetime, this is also true of Roth 401(k)s as of 2024. This feature can make them valuable tax- and estate-planning options.

There are several reasons to consider a Roth conversion this year or next. First, researching and preparing for a potential conversion now could mean you're well-positioned to act if volatility were to return to the stock market. That's because converting when stock prices are lower can help to lower the tax bill on converted pre-tax amounts.

While the new tax act made the current tax rates permanent, there’s no guarantee they won’t increase sometime in the future. In the meantime, a Roth conversion at current rates could potentially reduce what you might pay in taxes now compared to what you might owe if rates were to rise in the future. It could also potentially allow for qualified distributions in retirement that are tax-free and potentially eliminate the need for RMDs.4

Intrigued? Here are answers to common Roth conversion questions. Always consult a tax advisor about your specific circumstances.

Can I convert money from a traditional 401(k) to a Roth 401(k)?

Yes, if your plan offers a Roth 401(k) feature and allows in-plan conversions. Of course, taxes may still apply, depending on the source of the balances converted.

Tip: For more detail, see What to do with after-tax 401(k) contributions.

Can I convert money from a traditional 401(k) to a Roth IRA?

Yes, once retired or while still working if your plan permits in-service withdrawals from your 401(k). You can convert your traditional 401(k) either through a direct rollover to a Roth IRA or by rolling funds over to a traditional IRA, and then converting to a Roth IRA.

Tip: For more detail, see Converting your traditional IRA to a Roth IRA, which includes a Roth conversion tool and a checklist.

Can I convert to a Roth IRA even if I earn too much to contribute?

Yes, there are no income limits on conversion. Also, if you and/or your spouse have high income levels and are not eligible to contribute directly to a Roth IRA, and you do not already have a traditional IRA, you may want to consider opening a traditional IRA and making a nondeductible contribution, then converting it to a Roth IRA. This strategy is sometimes called a back-door Roth contribution.

Read Viewpoints on Fidelity.com: Do you earn too much for a Roth IRA?

How can I estimate my tax liability on an IRA conversion?

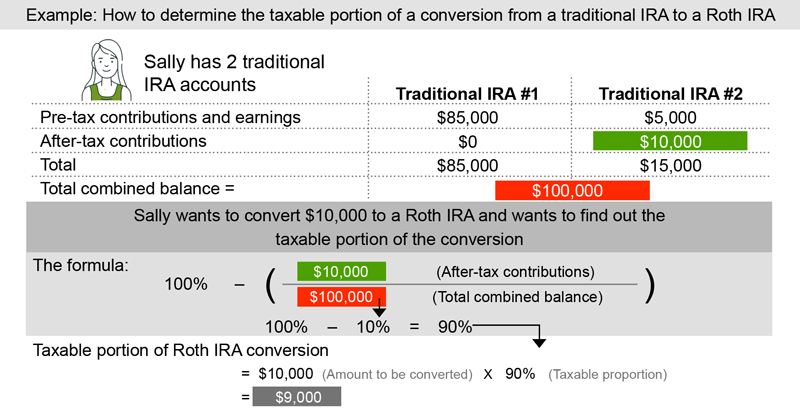

Remember, all the traditional IRAs you own (with the exception of inherited traditional IRAs) are considered one traditional IRA for tax purposes, no matter how many accounts you have. Your tax liability is based on 2 things: the taxable income generated by the conversion and your applicable tax rate.

To figure out how much of a conversion from a traditional IRA to a Roth IRA may be taxable, you'll need to know the types of contributions you made to all of your traditional IRAs. There are 2 types of contributions.

1. Pre-tax, or deductible contributions. These are contributions that are deducted from your taxable income for the tax year in which the contributions were made.

2. After-tax, or nondeductible contributions. Any contribution for which you do not take a tax deduction is known as a nondeductible contribution. Such contributions create what is sometimes called "basis" in your traditional IRA. The amount of these contributions is not included in taxable income for the purposes of a Roth IRA conversion.

Estimating the taxable income from a conversion is straightforward if you've never made nondeductible contributions to any traditional IRA. If that is the case, whatever amount you convert will all be taxable income.

Note that earnings are always taxable when converted, whether they are attributable to deductible or nondeductible contributions, so for purposes of figuring out taxes on a conversion, you can think of your balances as falling into just 2 categories: (1) nondeductible contributions, and (2) everything else.

According to IRS rules, you cannot cherry-pick and convert just nondeductible contributions, leaving deductible contributions and earnings in the account, in order to avoid taxes. Instead, you must figure out the proportion of your total traditional IRA balances across accounts that is composed of nondeductible contributions, then use that percentage to find out how much of your conversion will not be taxable. Note that inherited IRAs are excluded in this calculation.

Keep state taxes in mind too. A Roth IRA conversion is a taxable event. If your state has an income tax, the conversion will generally be treated as taxable income by your state as well as by the federal government.

Tip: If your spouse has IRAs with mostly nondeductible contributions and you have IRAs with mostly deductible contributions, you might consider converting your spouse's IRAs before yours to reduce the potential tax impact of conversion. The IRS views your IRA and your spouse’s independently for the above calculation.

How can I manage taxes on a Roth conversion?

Tax deductions can also help offset the tax cost of a Roth IRA conversion. For example, you may be able to take a tax deduction for donations to qualified charities. In general, by making charitable contributions with cash, you can deduct your charitable contribution up to 60% of your adjusted gross income (AGI) if you itemize. The deduction is usually limited to 30% of AGI for donations to some private foundations and other organizations, as well as for contributions of noncash assets. Note, however, that if your itemized deductions—which include charitable contributions—do not exceed the standard deduction, there wouldn't be any tax benefit from those charitable contributions. So be sure to consult with your tax advisor to plan your charitable strategy—there are techniques that can help ensure you enjoy the potential tax benefits of your charitable giving.

Learn more at FidelityCharitable.org

Does time of year matter?

Converting earlier in the year generally gives you more time to pay taxes. Taxes aren't due until the tax deadline of the following year, so you may have more than 15 months to pay the taxes on your converted balances if the conversion is small relative to your income. (Note: If you pay estimated taxes, you may need to make some payments sooner.)

But there are also some advantages to converting later in the year:

- You can still start the clock on the 5-year rule as of the beginning of the year. This IRS rule requires a waiting period of 5 years before withdrawing converted balances or you may pay a 10% penalty. But the clock starts on January 1 of the year you do the conversion—no matter when during the year it actually happened. The 5-year rule is counted separately for each conversion.

- You'll have more information about your income for the year. Since the amount you convert is considered taxable income, you may want to consider converting only the amount that would bring you to the top of your current tax bracket.

A conversion must be completed by December 31 to be included in that year's taxable income. Managing the tax impact of a Roth IRA conversion requires careful analysis. A review with a financial or tax advisor is always a good idea.

If I want to keep a specific stock or asset in my IRA in my portfolio for the long term, can I keep that asset and convert it to a Roth IRA?

Yes. If you are holding investments in a traditional IRA—ones you want to keep for a number of years—you can transfer those investments from your IRA to a Roth IRA. In terms of the taxes, there is no difference between transferring the investments and transferring their cash proceeds if sold in the IRA first.