After a rollercoaster year—from tariff volatility, to a bear scare, to a roaring market rebound—the US stock market has climbed back to new highs. In October, the current bull market marked its third birthday. And as of mid-December, the S&P 500® Index had returned almost 18% year to date in 2025.

But the big question now is whether this bull market will keep running in 2026. In my view, yes—but that outlook comes with some important caveats.

Where are the market and economic cycles?

The current US economic expansion—which began after the brief but severe contraction at the start of the pandemic in 2020—is now approaching its sixth year. That’s long by historical standards, and this economic cycle has been anything but typical. We’ve gone from pandemic lockdowns to massive stimulus, then to inflation and rising interest rates, and now to an AI-driven investment surge.

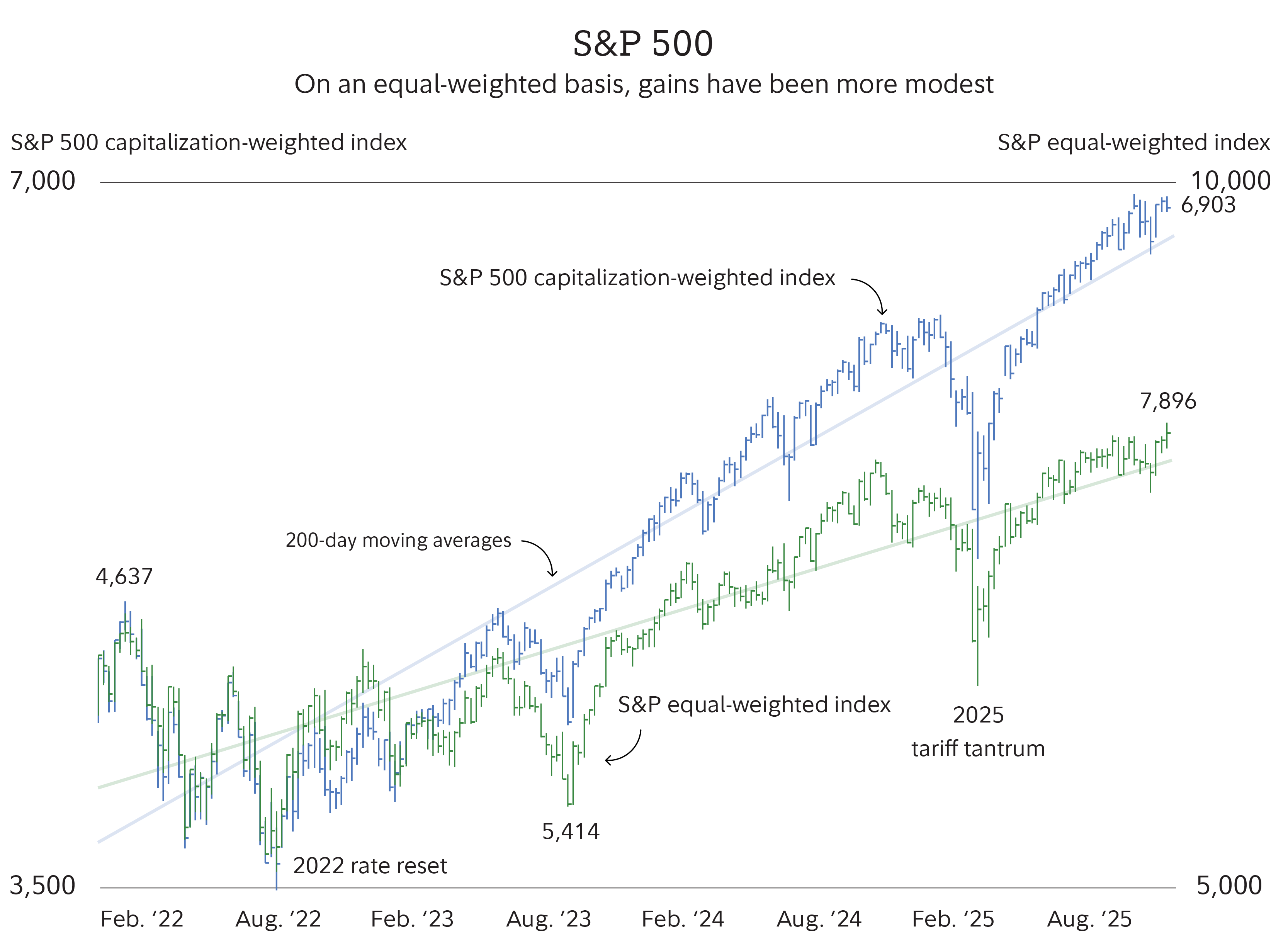

Of course, investors don’t measure bull and bear markets according to economic expansions and contractions. In 2022, stocks fell 28% over 9 months, which qualifies as a bear market by any standard. US stocks have been in a bull market ever since that low in October 2022. As of the S&P’s all-time high as of late last week, the index was up 91% since that 2022 low.

However, that gain might not be as impressive as it sounds. One reason for that is market concentration: This bull market’s gains have been disproportionately concentrated among a handful of mega-cap tech stocks—i.e., the “Magnificent 7.” Focusing on the equal-weighted S&P 500 (i.e., in which every stock receives the same weighting, and so larger companies do not have such an outsized impact) removes the impact of concentration. On that measure gains are still handsome, but more modest: 52% since the 2022 low.

The other reason is inflation. Stocks have historically provided positive long-term returns above the rate of inflation—helping to preserve and also grow investors’ purchasing power. And they have beaten inflation during this bull market, but the toll of inflation has been significant. In inflation-adjusted terms, the cap-weighted S&P is up a more modest 73%, while the equal-weighted S&P is up just 36%.

That last number seems surprisingly low, and shows what a significant effect market concentration and inflation have had on what has otherwise been an unimpressive bull.

What could drive stocks in 2026

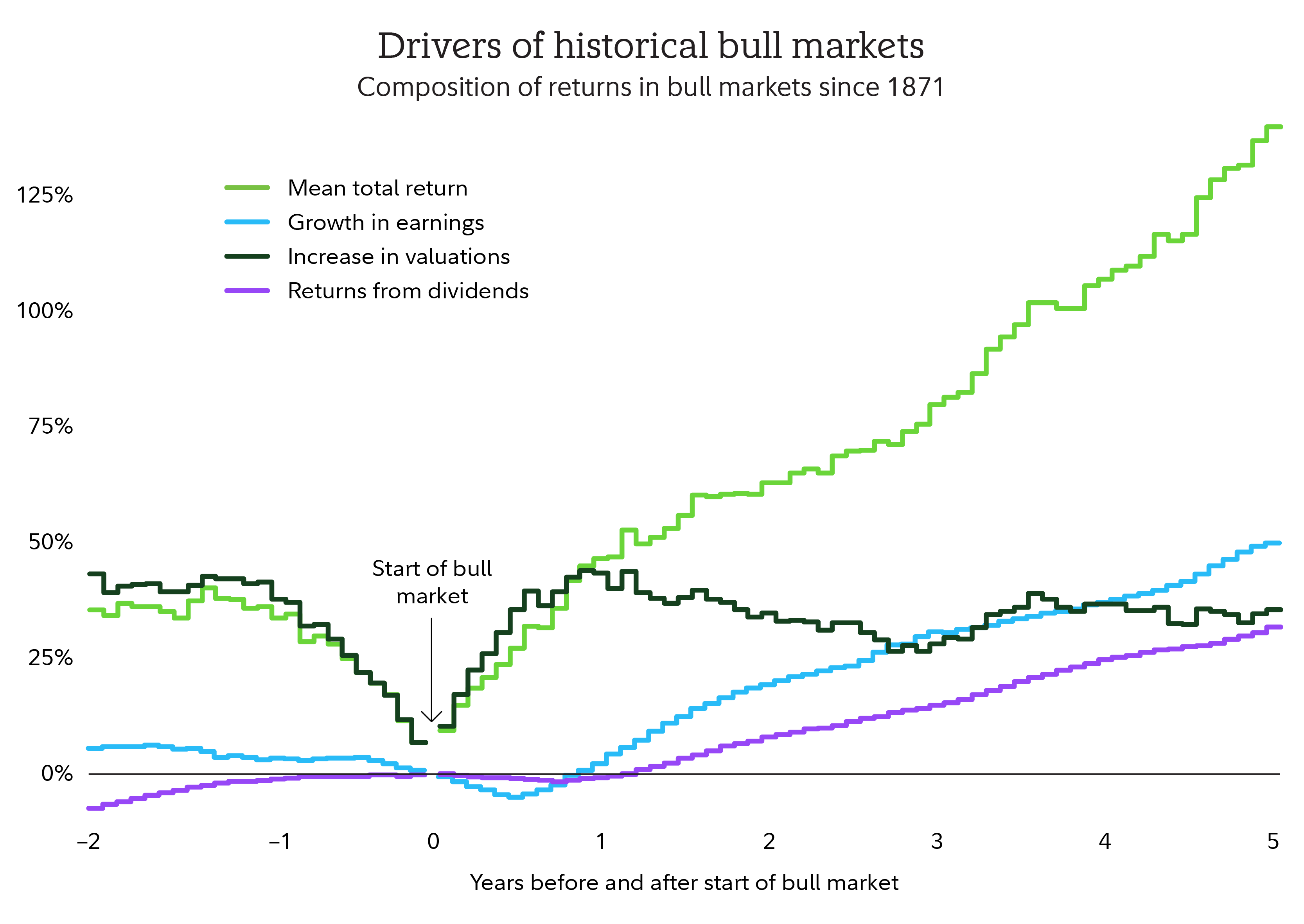

The current bull market began with rising P/E ratios, as is common given that stock prices typically bottom before earnings do. (By definition, if prices are rising but profits are falling, price-to-earnings ratios must be rising.) But in 2025, earnings growth took over as the dominant driver of returns, and this has been good to see as it generally signals a healthy market.

Historically, by year 3 of a bull market, earnings and valuations each account for about 40% of gains, with dividends making up the remaining 20%. That’s roughly where we are now.

This baton pass from valuations to earnings matters because growing earnings can signal a more sustainable market cycle. Analysts generally expect double-digit earnings growth for S&P 500 companies in 2026. If companies can deliver on those expectations, stocks could keep climbing.

Risks from valuations and interest rates

The risk is that the market is already priced for success—with generally high valuations reflecting a generally optimistic earnings outlook. At today’s prices, the market is essentially assuming profits will keep growing at a double-digit pace. If growth slows to its historical average of 6%–7%, valuations could come under pressure, which could in turn put stocks under pressure. Put simply: The more good news that’s already priced in to stock prices, the more susceptible the market could be to disappointments.

Another concern is interest rates. The Federal Reserve delivered on a final rate cut for 2025 at its most recent meeting. What the Fed will do in 2026 is unknowable and is particularly difficult to predict given that investors don’t yet know who the next Fed Chair will be. But markets show that investors generally expect additional cuts in the new year. However, inflation is still above the Fed’s 2% target—and hasn’t been at or below 2% in about 5 years. If the Fed takes a dovish turn next year, as some investors seem to expect, it could keep the economy running hot.

Why does that matter? A hot economy can put upward pressure on long-term interest rates, both due to higher expectations for economic growth and higher inflation expectations. And higher interest rates have tended to put downward pressure on stock prices and valuations (when bond yields rise, bonds become more attractive relative to stocks, and so stocks must reprice to stay attractive).

A 5% interest rate on 10-year Treasurys has been a key threshold for the market in recent years, with stocks suffering brief selloffs when the 10-year rate has neared that mark. That threshold could again be one to watch for in 2026.

My game plan for 2026

I believe the bull market is still intact and may persist in 2026, propelled by earnings growth and corporate investment spending. But I also recognize that the US market is already priced for success, and there is significant concentration risk.

What’s the solution? In my opinion, it’s to broaden one’s horizons, and look beyond just US mega caps. International stocks have had a strong year in 2025, and on several measures continue to look attractive. For example, earnings growth outside of the US is now better than in the US, giving investors compelling alternatives to the top-heavy S&P 500.

Beyond stocks, I’m cautious on long-term bonds, given those potential interest rate risks already mentioned (bond prices fall when interest rates rise). But I believe investments that are uncorrelated or less correlated to traditional stocks and bonds—such as certain alternative investments and commodities—could have a diversifying role in the year ahead.

(Learn more about why investors may need a new diversification in the current investing climate.)

The bottom line

2026 could be another positive year for stocks, but don’t ignore the risks. Valuations are high, concentration risk is real, and policy uncertainty looms. Diversification—across regions and asset classes—may matter more than ever.