Goal

To profit from a big price change – either up or down – in the underlying stock.

Explanation

A long strangle consists of one long call with a higher strike price and one long put with a lower strike. Both options have the same underlying stock and the same expiration date, but they have different strike prices. A long strangle is established for a net debit (or net cost) and profits if the underlying stock rises above the upper break-even point or falls below the lower break-even point. Profit potential is unlimited on the upside and substantial on the downside. Potential loss is limited to the total cost of the strangle plus commissions.

Example of long strangle

| Buy 1 XYZ 105 call at | (1.50) |

| Buy 1 XYZ 95 put at | (1.30) |

| Net cost = | (2.80) |

Maximum profit

Profit potential is unlimited on the upside, because the stock price can rise indefinitely. On the downside, profit potential is substantial, because the stock price can fall to zero.

Maximum risk

Potential loss is limited to the total cost of the strangle plus commissions, and a loss of this amount is realized if the position is held to expiration and both options expire worthless. Both options will expire worthless if the stock price is equal to or between the strike prices at expiration.

Breakeven stock price at expiration

There are two potential break-even points:

- Higher strike price plus total premium: In this example: 105.00 + 2.80 = 107.80

- Lower strike price minus total premium: In this example: 95.00 – 2.80 = 92.20

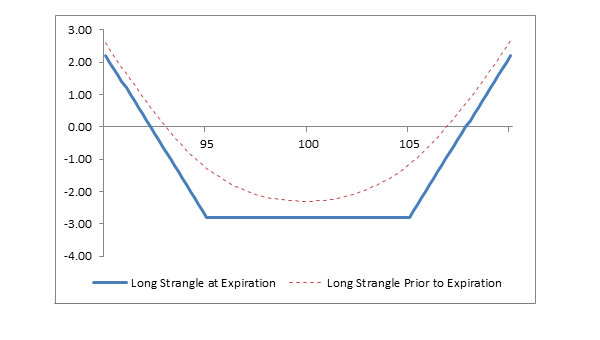

Profit/Loss diagram and table: long strangle

| Long 1 105 call at | (1.50) |

| Long 1 XYZ 95 put at | (1.30) |

| Net cost = | (2.80) |

| Stock Price at Expiration | Long 105 Call Profit/(Loss) at Expiration | Long 95 Put Profit/(Loss) at Expiration | Long Strangle Profit / (Loss) at Expiration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 110 | +3.50 | (1.30) | +2.20 |

| 109 | +2.50 | (1.30) | +1.20 |

| 108 | +1.50 | (1.30) | +0.20 |

| 107 | +0.50 | (1.30) | (0.80) |

| 106 | (0.50) | (1.30) | (1.80) |

| 105 | (1.50) | (1.30) | (2.80) |

| 104 | (1.50) | (1.30) | (2.80) |

| 103 | (1.50) | (1.30) | (2.80) |

| 102 | (1.50) | (1.30) | (2.80) |

| 101 | (1.50) | (1.30) | (2.80) |

| 100 | (1.50) | (1.30) | (2.80) |

| 99 | (1.50) | (1.30) | (2.80) |

| 98 | (1.50) | (1.30) | (2.80) |

| 97 | (1.50) | (1.30) | (2.80) |

| 96 | (1.50) | (1.30) | (2.80) |

| 95 | (1.50) | (1.30) | (2.80) |

| 94 | (1.50) | (0.30) | (1.80) |

| 93 | (1.50) | +0.70 | (0.80) |

| 92 | (1.50) | +1.70 | +0.20 |

| 91 | (1.50) | +2.70 | +1.20 |

| 90 | (1.50) | +3.70 | +2.20 |

Appropriate market forecast

A long strangle profits when the price of the underlying stock rises above the upper breakeven point or falls below the lower breakeven point. The ideal forecast, therefore, is for a “big stock price change when the direction of the change could be either up or down.” In the language of options, this is known as “high volatility.”

Strategy discussion

A long – or purchased – strangle is the strategy of choice when the forecast is for a big stock price change but the direction of the change is uncertain. Strangles are often purchased before earnings reports, before new product introductions and before FDA announcements. These are typical of situations in which “good news” could send a stock price sharply higher, or “bad news” could send a stock price sharply lower. The risk is that the announcement does not cause a significant change in stock price and, as a result, both the call price and put price decrease as traders sell both options.

It is important to remember that the prices of calls and puts – and therefore the prices of strangles – contain the consensus opinion of options market participants as to how much the stock price will move prior to expiration. This means that buyers of strangles believe that the market consensus is “too low” and that the stock price will move beyond a breakeven point – either up or down.

The same logic applies to options prices before earnings reports and other such announcements. Dates of announcements of important information are generally publicized in advanced and well-known in the marketplace. Furthermore, such announcements are likely, but not guaranteed, to cause the stock price to change dramatically. As a result, prices of calls, puts and strangles frequently rise prior to such announcements. In the language of options, this is known as an “increase in implied volatility.”

An increase in implied volatility increases the risk of trading options. Buyers of options have to pay higher prices and therefore risk more. For buyers of strangles, higher options prices mean that breakeven points are farther apart and that the underlying stock price has to move further to achieve breakeven. Sellers of strangles also face increased risk, because higher volatility means there is a greater probability of a big stock price change and, therefore, a greater probability that an option seller will incur a loss.

“Buying a strangle” is intuitively appealing, because “you can make money if the stock price moves up or down.” The reality is that the market is often “efficient,” which means that prices of strangles frequently are an accurate gauge of how much a stock price is likely to move prior to expiration. This means that buying a strangle, like all trading decisions, is subjective and requires good timing for both the buy decision and the sell decision.

Impact of stock price change

When the stock price is between the strike prices of the strangle, the positive delta of the call and negative delta of the put very nearly offset each other. Thus, for small changes in stock between the strikes, the price of a strangle does not change very much. This means that a strangle has a “near-zero delta.” Delta estimates how much an option price will change as the stock price changes.

However, if the stock price “rises fast enough” or “falls fast enough,” then the strangle rises in price. This happens because, as the stock price rises, the call rises in price more than the put falls in price. Also, as the stock price falls, the put rises in price more than the call falls. In the language of options, this is known as “positive gamma.” Gamma estimates how much the delta of a position changes as the stock price changes. Positive gamma means that the delta of a position changes in the same direction as the change in price of the underlying stock. As the stock price rises, the net delta of a strangle becomes more and more positive, because the delta of the long call becomes more and more positive and the delta of the put goes to zero. Similarly, as the stock price falls, the net delta of a strangle becomes more and more negative, because the delta of the long put becomes more and more negative and the delta of the call goes to zero.

Impact of change in volatility

Volatility is a measure of how much a stock price fluctuates in percentage terms, and volatility is a factor in option prices. As volatility rises, option prices – and strangle prices – tend to rise if other factors such as stock price and time to expiration remain constant. Therefore, when volatility increases, long strangles increase in price and make money. When volatility falls, long strangles decrease in price and lose money. In the language of options, this is known as “positive vega.” Vega estimates how much an option price changes as the level of volatility changes and other factors are unchanged, and positive vega means that a position profits when volatility rises and loses when volatility falls.

Impact of time

The time value portion of an option’s total price decreases as expiration approaches. This is known as time erosion, or time decay. Since long strangles consist of two long options, the sensitivity to time erosion is higher than for single-option positions. Long strangles tend to lose money rapidly as time passes and the stock price does not change.

Risk of early assignment

Owners of options have control over when an option is exercised. Since a long strangle consists of one long, or owned, call and one long put, there is no risk of early assignment.

Potential position created at expiration

There are three possible outcomes at expiration. The stock price can be at a strike price or between the strike prices of a long strangle, above the strike price of the call (the higher strike) or below the strike price of the put (the lower strike).

If the stock price is at a strike price or between the strike prices at expiration, then both the call and the put expire worthless and no stock position is created.

If the stock price is above the strike price of the call (the higher strike) at expiration, the put expires worthless, the long call is exercised, stock is purchased at the strike price and a long stock position is created. If a long stock position is not wanted, the call must be sold prior to expiration.

If the stock price is below the strike price of the put (lower strike) at expiration, the call expires worthless, the long put is exercised, stock is sold at the strike price and a short stock position is created. If a short stock position is not wanted, the put must be sold prior to expiration.

Note: options are automatically exercised at expiration if they are one cent ($0.01) in the money. Therefore, if the stock price is “close” to one of the strike prices of a strangle as expiration approaches, and if the owner of a strangle wants to avoid having either a long or short stock position, the long stock in danger of being exercised automatically must be sold prior to expiration.

Other considerations

Long strangles are often compared to long straddles, and traders frequently debate which is the “better” strategy.

Long strangles involve buying a call with a higher strike price and buying a put with a lower strike price. For example, buy a 105 Call and buy a 95 Put. Long straddles, however, involve buying a call and put with the same strike price. For example, buy a 100 Call and buy a 100 Put.

Neither strategy is “better” in an absolute sense. There are tradeoffs.

There are two advantages and two disadvantages of a long strangle. The first advantage is that the cost and maximum risk of one strangle (one call and one put) are lower than for one straddle. Second, for a given amount of capital, more strangles can be purchased. The first disadvantage is that the breakeven points for a strangle are further apart than for a comparable straddle. Second, there is a greater chance of losing 100% of the cost of a strangle if it is held to expiration. Thus, when there is little or no stock price movement, a long strangle will experience a greater percentage loss over a given time period than a comparable straddle.

A long straddle has two advantages and two disadvantages. The first advantage is that the breakeven points are closer together for a straddle than for a comparable strangle. Second, there is less of a change of losing 100% of the cost of a straddle if it is held to expiration. The first disadvantage of a long straddle is that the cost and maximum risk of one straddle are greater than for one strangle. Second, for a given amount of capital, fewer straddles can be purchased.