Expense ratios (ERs) may not be on your radar when you're investing in ETFs or mutual funds—but they should be. That's because fund expense ratios can have a meaningful impact on your long-term returns. Learn why with this breakdown on expense ratios.

What is an expense ratio?

An expense ratio is a fee investors pay to the service providers of their mutual fund or exchange-traded fund that covers management, administrative, custodial, marketing, legal, and accounting costs, among other costs. It's basically the cost to ride. You'll typically see an expense ratio as a percentage of your overall investment in that fund. For example, say a fund charges a 0.50% ER. That means you'll pay $5 annually for every $1,000 invested in that fund. An expense ratio can also be shown in a fund's prospectus as a dollar amount based on a hypothetical $10,000 initial investment.

When researching a fund's expense ratio, you may see two different percentages: a gross expense ratio and a net expense ratio. The gross expense ratio is the total annual fund or class operating expenses (before waivers or reimbursements) paid by the fund and stated as a percent of the fund's total net assets. The net expense ratio takes the gross ratio and removes any discounts or waived fees and/or expense reimbursements that may apply.

How does an expense ratio work?

Funds typically pay regular operating expenses out of fund assets, rather than charge investors separately. These fees include costs associated with portfolio management (paying the team buying and selling investments that make up the fund), marketing, administration, accounting, and reporting.

You won't see a deduction of cash or shares from your brokerage account to pay these fees. Instead, they're automatically taken out of the fund's net assets. Fees are factored into the daily net asset value (NAV), which is the price per share of the fund, and expenses are factored into the returns of the fund.

Why is an expense ratio important?

An expense ratio is important because this ongoing cost represents the portion of your investment's value you won't get to keep. Just as your investment returns may compound over time, so can investment fees. Although you might not notice a total expense ratio's impact on your returns in a single year, over decades of investing, a high expense ratio can eat away at your profits.

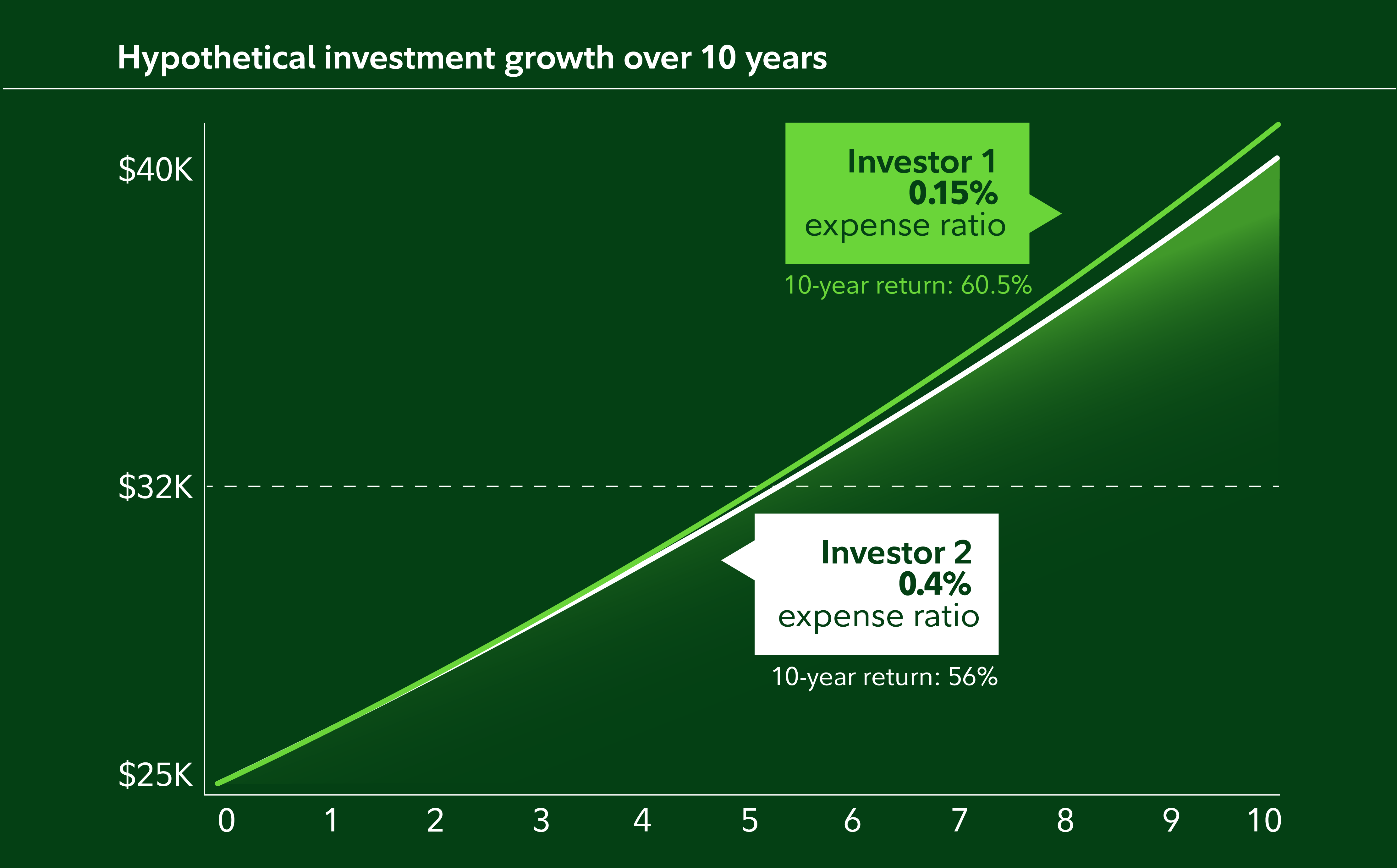

Here's a hypothetical example: Let's say there are two investors who each bought $25,000 of two similar funds with different expense ratios, at 0.15% and 0.4% respectively. Over 10 years, let's assume the expense ratios of these funds remain the same, and that each fund grows 5% annually prior to expenses factored in (aka net of fees). Rounded to the nearest dollar, these values would be the following:

| Investor 1 (0.15% expense ratio) | Investor 2 (0.4% expense ratio) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Value at beginning of year | Year | Value at beginning of year |

| 0 | $25,000 | 0 | $25,000 |

| 1 | $26,211 | 1 | $26,145 |

| 2 | $27,480 | 2 | $27,342 |

| 3 | $28,811 | 3 | $28,595 |

| 4 | $30,206 | 4 | $29,904 |

| 5 | $31,668 | 5 | $31,274 |

| 6 | $33,202 | 6 | $32,706 |

| 7 | $34,810 | 7 | $34,204 |

| 8 | $36,495 | 8 | $35,771 |

| 9 | $38,263 | 9 | $37,409 |

| 10 | $40,116 | 10 | $39,122 |

| 10-year cumulative return | 60.5% | 10-year cumulative return | 56% |

Expense ratios for different types of funds

Expense ratios can vary depending on how the fund is managed (actively or passively) and how it's structured (as an ETF or a mutual fund).

Active vs. passive fund expense ratios

A primary influence of a fund's expense ratio is the fund's management style. Actively managed funds have a team of financial professionals conducting research to inform their investment decisions. For that extra work, they typically charge a higher management fee (which is a component of the expense ratio) than passively managed funds. Passive funds generally instead use technology in an attempt to mirror the performance of an area of the market.

ETF expense ratios

ETFs can be either actively or passively managed, and their expense ratios typically reflect that. A good number of ETFs are passively managed index funds. For example, this means they aim to replicate the performance of a group of stocks, like the S&P 500®, which tracks the performance of about 500 of the largest companies in the US. A rising number of ETFs use more active strategies and may have higher expense ratios to match.

Mutual fund expense ratios

Because historically many mutual funds are actively managed and many ETFs were historically passively managed, you may see higher expense ratios, on average, in mutual funds. That higher expense ratio helps pay for the professional expertise that goes into selecting investments. However, there are also mutual funds that seek to track the performance of an index and have comparable or lower expense ratios than their ETF counterparts.

Expense ratio formula

The formula to determine an expense ratio is simple, though you won't have to do the math yourself. All funds are required by law to disclose their expense ratios. Still, here's the expense ratio formula:

Expense ratio (%) = Total fund operating costs / Fund average net assets

What is an average expense ratio?

Knowing average expense ratios could be helpful context when researching funds. In 2024, the average expense ratio for equity mutual funds was 0.40%; for bond mutual funds, it was 0.38%.1 Among ETFs, the average expense ratio in 2024 was 0.14% for equity ETFs and 0.10% for bond ETFs.2 You could compare a fund's total expense ratio to similar funds with similar goals for more specific comparisons.

It's important to remember that a fund's expense ratio is just a single factor to consider when choosing an investment option. Remember to also consider a fund's investment objectives, strategy, and risks. Make sure to contextualize the investment with your risk tolerance and time horizon, and don't hesitate to contact an investment professional to discuss what investment options may be appropriate for your financial situation.

How to research expense ratios

Whether an expense ratio makes sense for you depends on your investment goals, whether you pick an actively or passively managed ETF or mutual fund, and how that number measures up to similar funds' expense ratios. If you're curious how to research total expense ratios at Fidelity, here's a step-by-step guide:

- Use the right tool: You can research different funds' expense ratios in our Mutual Funds Research tool or ETF screener at Fidelity.

- Narrow your search: You could filter by asset classes you want in your fund (like bonds and stocks, which are called equities in the tools), the management approach you want (called passive index or active in the tools), and issuer, like Fidelity.

- Compare expense ratios: With a handful of similar funds selected, look at each option's fund overview. On the ETF screener, you'll see net expense ratios on the “Search Criteria” tab. On the Mutual Funds Research tool, you'll see net and gross expense ratios if you scroll to the right on the “Overview” tab.