Diversification is hardly a novel concept: By holding a wide variety of investments, investors have a better shot at ensuring that at any given time, there’s at least some part of their portfolio delivering positive returns. While diversification does not ensure a profit or guarantee against loss, holding some investments that zig when others zag can help smooth out the ride a portfolio delivers—helping investors stick with their strategy and stay on track to meet their goals.

Yet for the past decade-plus, diversification has started to look like an expensive—and perhaps even unnecessary—form of insurance. US stocks delivered a commanding 14.6% annualized return over the past 10 years, as measured by the S&P 500 Index®.1 Non-US stocks trailed by 7 percentage points per year on average, while US bonds lagged by more than 12 percentage points—returning less than 2% per year on average.2

Such a wide performance discrepancy might lull investors into overlooking the insurance-like value of diversification. But just because a 10-year flood hasn’t struck in the past decade doesn’t mean one won’t in the next.

In fact, due to powerful currents of change brewing in the investing climate, investors may find they need both old and new forms of diversification to help protect their portfolios in 2026 and beyond.

A climate of new risks

High and rising government debt and deficits—in the US and throughout the developed world—may be creating the conditions for new sources of risk and volatility that could impact markets and investors’ portfolios in the coming years, according to research from Fidelity’s Asset Allocation Research Team (AART).

Like diversification, concern over US government debt is hardly anything new. Federal debt as a percent of gross domestic product (GDP) has been rising since the 1970s. Concerns over government debt in the 1980s led to the creation of the US national debt clock in Manhattan in 1989. Yet for much of the 21st century, low interest rates allowed the US government to continue running large deficits without adverse effects.

But the pressures of US indebtedness have been escalating in recent years, says Irina Tytell, team leader with Fidelity’s AART. The federal government spent heavily in response to COVID, and before that, the Global Financial Crisis. Tax cuts of the last 10 years have curtailed federal revenues. And the higher level of interest rates since 2022 has increased the cost of carrying debt.

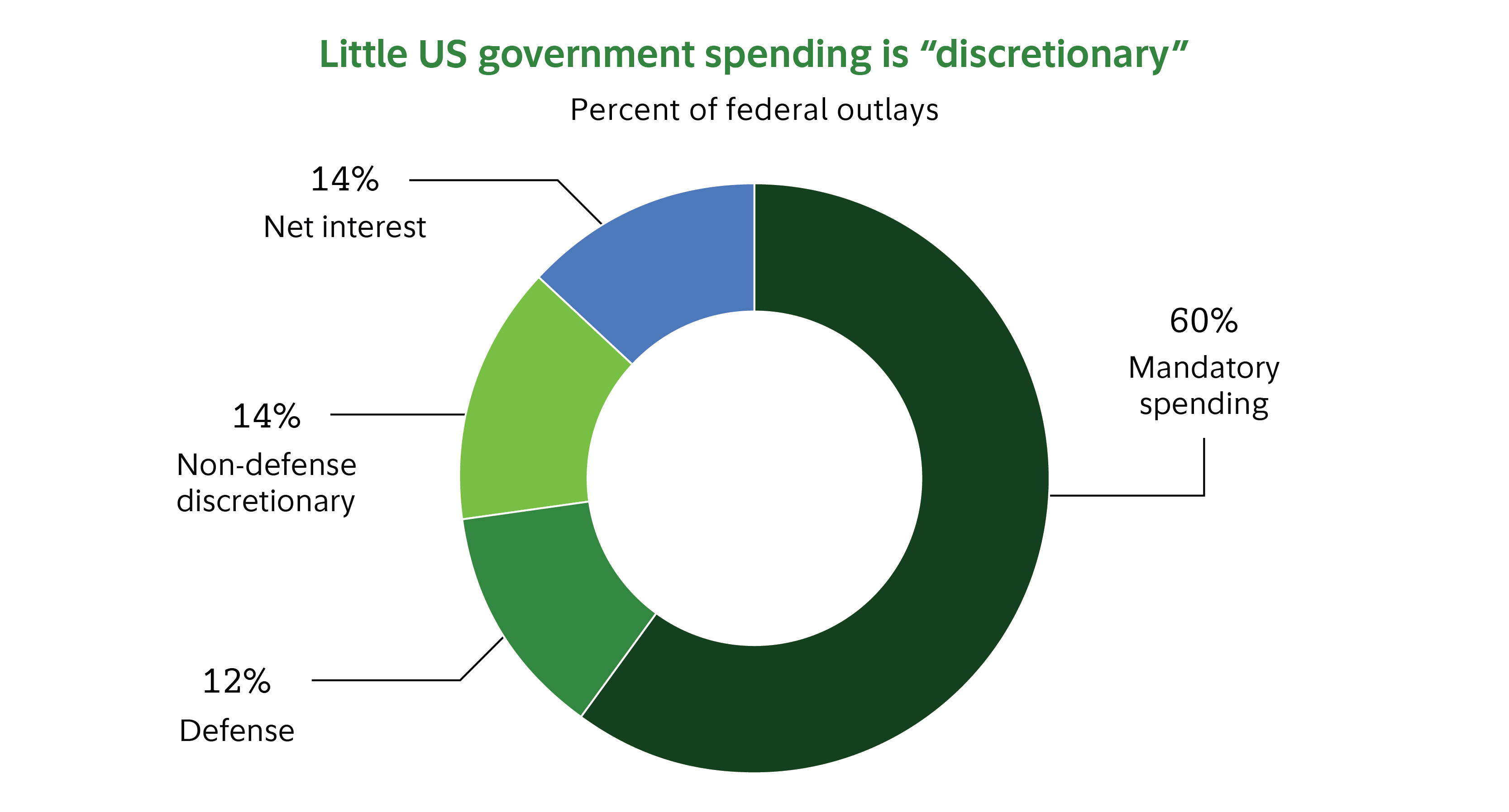

In 2024, the cost of interest on the federal debt outpaced defense spending for the first time—a trend that is not projected to reverse. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the cost of interest alone is now nearly in line with all federal discretionary nondefense spending and is projected to outpace it in the next 10 years—making it increasingly challenging to reverse the trajectory of federal debt with discretionary spending cuts.3 This means high ongoing US deficits could become a more immediate source of volatility for markets, rather than a distant one.

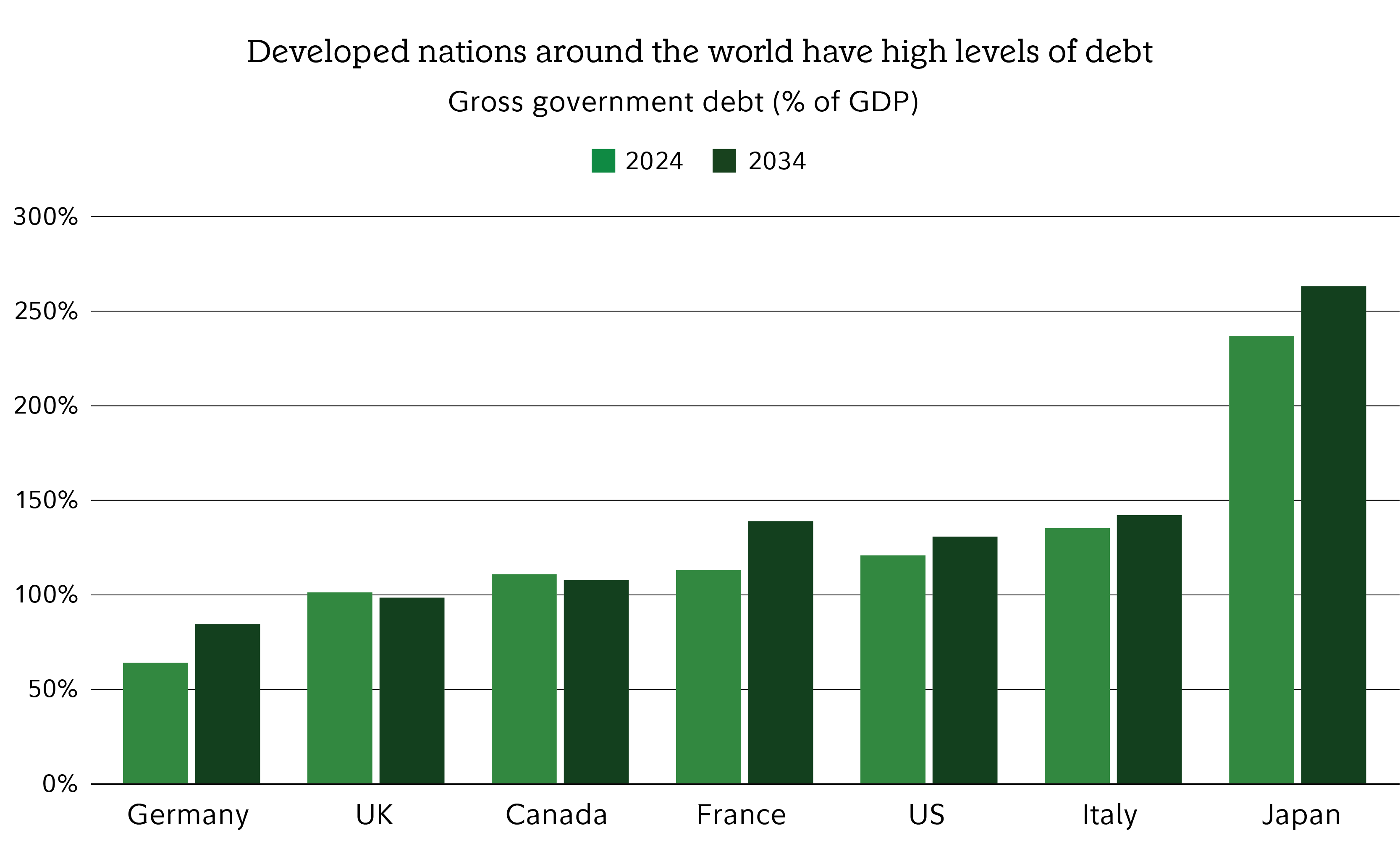

The picture in the rest of the developed world is similarly challenging. As the chart below shows, 6 of the 7 G7 nations already face debt-to-GDP ratios of around 100% or more.

“This is not just a US problem,” says Dirk Hofschire, managing director of Fidelity’s AART. “It’s a global problem, and many other developed countries are in the same boat.”

How high indebtedness might increase volatility

The implications of high debt burdens are complex and interconnected. Some of the ways it might foster volatility include by straining the Fed’s ability to make independent policy decisions, limiting the government’s ability to respond to future crises, creating volatility in the Treasury market, and sowing the seeds of higher long-term inflation.

Pressure on the Fed to keep interest rates low

The Fed's mandate is to keep inflation low and stable, while also keeping unemployment low. At times, the Fed has enacted policies that are unpopular or that caused short-term pain, in order to pursue these goals. For example, hiking interest rates in 2022 helped rein in 9% inflation, but likely contributed to a bear market in stocks.

High levels of national debt and high interest expense may put pressure on the Fed to hold interest rates low simply so that the US can finance its debts, regardless of the needs of the broader economy. This could mean holding down the fed funds rate—the overnight interest rate that the Fed controls directly. It could also mean intervening in the bond market to hold down interest rates that it does not directly control (also known as “financial repression”). But many economists believe that holding interest rates artificially low has the potential to lead to higher inflation.

Limiting the ability to respond to future crises

Federal government policy provides key tools that can help smooth out the economy’s bumps—mitigating crises and softening economic downturns. Fiscal policy, meaning actions controlled by Congress and the president, can include sending out stimulus checks, authorizing new lending programs, or providing other cushioning to people and businesses in a crisis. Monetary policy, meaning adjustments to interest rates by the Fed, can help accelerate the economy to lift it out of a downturn faster.

High federal debt can limit the use of both tools, says Tytell. If the federal government’s finances are already strained, there may be less appetite or ability to increase spending further (and issue new debt) in a crisis. And if interest rates are already low due to financial repression, the Fed may have little or no room to cut them further. “In this environment, policymakers could be more limited in their ability to help the real economy, and policy could be more prone to create further fluctuations and instability,” says Tytell.

Volatility in the Treasury market

As the US becomes more indebted it must issue more Treasury debt—creating more supply of Treasury bonds, notes, and bills. Over time, investors may start demanding higher yields to keep buying this debt. Spikes in Treasury yields can create spillover volatility in the stock market. Higher yields can also exacerbate the cost of funding the government's debt. Less likely—but not impossible—could be a crisis of confidence in the US dollar or in the government’s ability to pay its debts.

Higher long-term inflation

Less dramatic—but perhaps most likely of all—is the possibility that high debt and deficits could set the stage for a long-term period of higher inflation. High deficits do not themselves create inflation. But they can create incentives for policymakers to pursue inflationary policies. For example, keeping interest rates artificially low can help stoke inflation.

Fidelity’s Asset Allocation Research Team conducted a study of developed economies that experienced debt-to-GDP ratios of 100% (a threshold the US has been nearing). Inflation was a key tool among countries that were successful in subsequently reducing their debt ratios—with 80% of such countries experiencing an inflation rate of more than 4% in the following decade.

The challenge—and opportunity—for investors

In the face of these headwinds, it can be tempting to catastrophize or jump to pessimistic conclusions. But for investors, perhaps the most crucial move to make is to accept that they don’t know what they don’t know.

These forces may create new risks and unknowns, but they don’t point to any predetermined conclusion. While it may be challenging to stay invested in the face of these risks, going to cash could prove to be a far riskier move in the face of potentially higher inflation. Over long periods, markets and the US economy have shown an astonishing ability to surmount obstacles and find their way back to long-term growth.

Instead, investors have an opportunity to diversify their diversifiers—by adding certain investments that perform differently than traditional stocks and bonds. Some of these diversifiers might perform particularly well as inflation hedges. Others might provide support in certain specific unique environments—acting as shock absorbers when other investments might struggle.

What is the new diversification?

The new diversification does not mean throwing out your stocks or bonds. Stocks remain the primary growth engine of a portfolio, and they have historically been strong long-term inflation hedges. Bonds still serve the important role of ballast in a portfolio. And in recent years bond yields have risen, improving their long-term return potential.

But it does mean making sure that you are widely diversified within those broad asset classes, and perhaps even incorporating certain investments that don’t fit neatly into either of those categories. Those may include the following:

International investments

International stocks have gained 26% in dollar terms in 2025 as of late November, showing how powerfully a weakening dollar can boost the value of non-US-dollar investments.4 High debt levels could contribute to further weakness in the dollar through higher inflation and if foreign investors seek to diversify away from the US.

Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS)

TIPS are Treasury-issued bonds with principal values that rise in line with inflation. Because the interest they pay is tied to that principal value, the dollar amount of their interest payments rises with inflation as well. They can play a valuable role in a portfolio thanks to their ability to hedge against a certain specific type of risk: unexpected inflation spikes. “TIPS have historically shined when inflation has been a surprise,” says Naveen Malwal, institutional portfolio manager with Strategic Advisers, LLC, the investment manager for many of Fidelity’s managed accounts.

Alternative investments

Alternative investments include opportunities beyond traditional investments like stocks, bonds, and cash. Types of alternative investments include real assets, commodities, private equity, private credit, digital assets, and liquid alternatives.

Investors should do their due diligence when it comes to alternative investments because they may feature different and greater risks than traditional investments—such as more complexity, shorter track records, more volatility, and/or less liquidity. But for some investors, a small allocation to certain alternative investments may be both in line with their goals and risk tolerance, and could provide a source of returns that performs differently from traditional investments like stocks and bonds.

Real assets

Real assets are a type of alternative investment and can include any tangible physical assets—including commercial and residential real estate, infrastructure, commodities, and natural resources such as timberland. Real estate has historically been one of the best-performing asset classes in periods of high inflation.5 “If inflation is accelerating, often the value of land or buildings is rising as well,” explains Malwal. Investors can access real assets in the public market, such as with real estate investment trusts (REITs) that trade on major stock exchanges, or in the private market, such as with private real estate investments.

Commodity-related investments

Commodities are another type of alternative investment, and can mean everything from precious metals (gold, silver, and platinum), to energy (oil and gas), to agricultural resources (cocoa, cattle, corn, and more), to industrial metals and rare-earth minerals. Many commodity-related investments can provide further inflation-hedging potential, because a rise in inflation often goes hand-in-hand with rising commodity prices. However, commodity investments can be volatile, so caution is warranted.

The new diversification in practice

Malwal notes that Strategic Advisers has been leaning more into such investments in certain client portfolios in the last 1 to 2 years. However, the overall allocation to such diversifiers is still relatively small.

“Bringing in too much of these other asset classes could change a portfolio’s risk profile,” Malwal says. “Strategic Advisers believes they work in concert with major building blocks like US and international stocks, investment-grade bonds, and short-term investments.”

For a well-diversified portfolio that typically targets a 60% allocation to stocks and 40% allocation to bonds, Strategic Advisers has carved out about 6% of their clients' portfolios for other diversifiers. These have included TIPS, commodities, real assets, high-yield bonds, and alternative investments—with the bulk of that coming out of the allocation to traditional bonds. Bonds have historically provided lower diversification benefits when inflation is rising, and so could be less effective at managing stock market volatility in this environment.

He also notes that his team is cautious and selective in choosing which specific investments it uses to provide these allocations—avoiding choices with limited liquidity, short track records, or excessive volatility.

An outlook rich with complexity—and opportunity

The precise nature of tomorrow’s risks, and whether any single investment will prove a silver bullet, is unknowable. But what investors can do today is create a long-term plan that’s suited to their time horizon, goals, and risk tolerance—and to make sure that plan includes a well-rounded mix of portfolio defenses.

If you need help creating a portfolio that’s resilient in the face of new challenges, without sacrificing long-term growth potential, learn more about how we can work together.