The potential economic impact of artificial intelligence (AI) is a subject of great debate, with many predicting that it could potentially transform the way we live and work. But what does the future really hold for this technology and what should investors be doing about it? To get a better sense of the potential impact of AI, it’s important to consider the data.

While we can't predict the future, history may provide some insight into AI’s economic prospects in the long run. According to Irina Tytell, an economist and team leader on Fidelity’s Asset Allocation Research Team (AART), it might be possible to estimate the effect that AI could potentially have on labor productivity and profits in the coming years. By gauging historical capital investment patterns and examining the adoption of important technological innovations of the past, we may be able to develop a more informed perspective on what to expect from AI in the next 5, 10, or 20 years—and better appreciate how much uncertainty still surrounds it.

What is AI?

When discussing AI, it’s crucial that we be clear about exactly what it is we’re talking about.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a general term that encompasses technologies capable of accomplishing tasks that typically would have required human reasoning to achieve. Within AI, “machine learning” refers to processes that operate without explicit programming—in essence, these technologies make decisions on their own, based on learnings they have synthesized from large sets of data. “Generative AI,” perhaps best known through tools like ChatGPT, is an application of artificial intelligence, using patterns found within those large datasets to create original content, such as text, images, or video, on the fly.

AI technology may show great potential in a variety of sectors, with a wide-ranging set of possible applications, such as powering chatbots and voice-activated personal assistants; writing and summarizing content or computer code; and improving the speed and accuracy of medical diagnoses. Given the potential efficiencies and significant improvements in productivity these applications may represent, it’s no surprise that many companies—and investors—have taken an interest.

But how realistic are these expectations, and when might the impact of AI be seen in the broader economy? According to a December 2024 survey, only 6.3% of businesses reported using AI tools, and a number of important headwinds may still need to be addressed before AI can reach widespread adoption.2

What might slow the adoption of AI technologies?

While new technologies always face challenges, 4 in particular stand out when discussing AI.

Financial costs

"In terms of digital technology, AI may be the most expensive one we’ve ever had," says Tytell. To date, the cost of standing up an AI platform has been substantial. OpenAI’s GPT-4 is estimated to have cost over $78 million to train.3 Tytell also notes that data costs, which have largely not been a factor to date, could also rise in the future. "These models have already consumed most of the free data that’s available," she says. "If they need access to more data, where is that going to come from and who is going to pay for it?"

Environmental costs

It is estimated that training OpenAI’s GPT-3 took 1,287 MWh, or about as much electricity as 120 US households consume in a year, and generated 552 metric tons of carbon emissions.4 This does not include the additional power needed to facilitate use of the model on an ongoing basis. While new advances in AI may alleviate this somewhat going forward, it’s possible that more efficient models may lead to an overall increase in power demand. This could still constrain adoption—and draw the attention of regulators.

The impact on workers

"AI is a labor-saving technology," says Tytell. “By definition, such technologies tend to displace certain workers. On the other hand, they can strengthen the prospects of occupations that are complementary to the technology and perhaps create new jobs, as well." In fact, according to one analysis of US Census data, more than 60% of jobs today did not exist before World War II.5 "New jobs are what power the labor market in the long run," says Tytell.

Fear, uncertainty, and doubt

There are many questions about the accuracy and reliability of AI outputs, as well as legal uncertainties with regard to copyright (for generative AI models), discrimination (when used in hiring), data privacy, and cybersecurity. In short, there’s still a lot we don’t know. "In a high-stakes environment where accuracy is really important, it’s likely that adoption will be limited until these issues are improved sufficiently," says Tytell.

Furthermore, Tytell cautions, it’s simply not easy to roll out a new technology—it takes time and effort. "The need to invest capital both in order to make use of the technology and to educate workers on how to use it most effectively is significant," says Tytell. "Because of that, it could take a while to see the productivity gains."

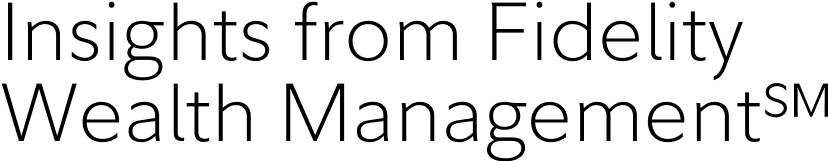

Looking back at the development of other technologies that required changes in worker skills and business practices, we can see that adoption was a slow and methodical process—in some cases taking as long as 20 years to achieve 50% penetration.

How might AI impact the economy?

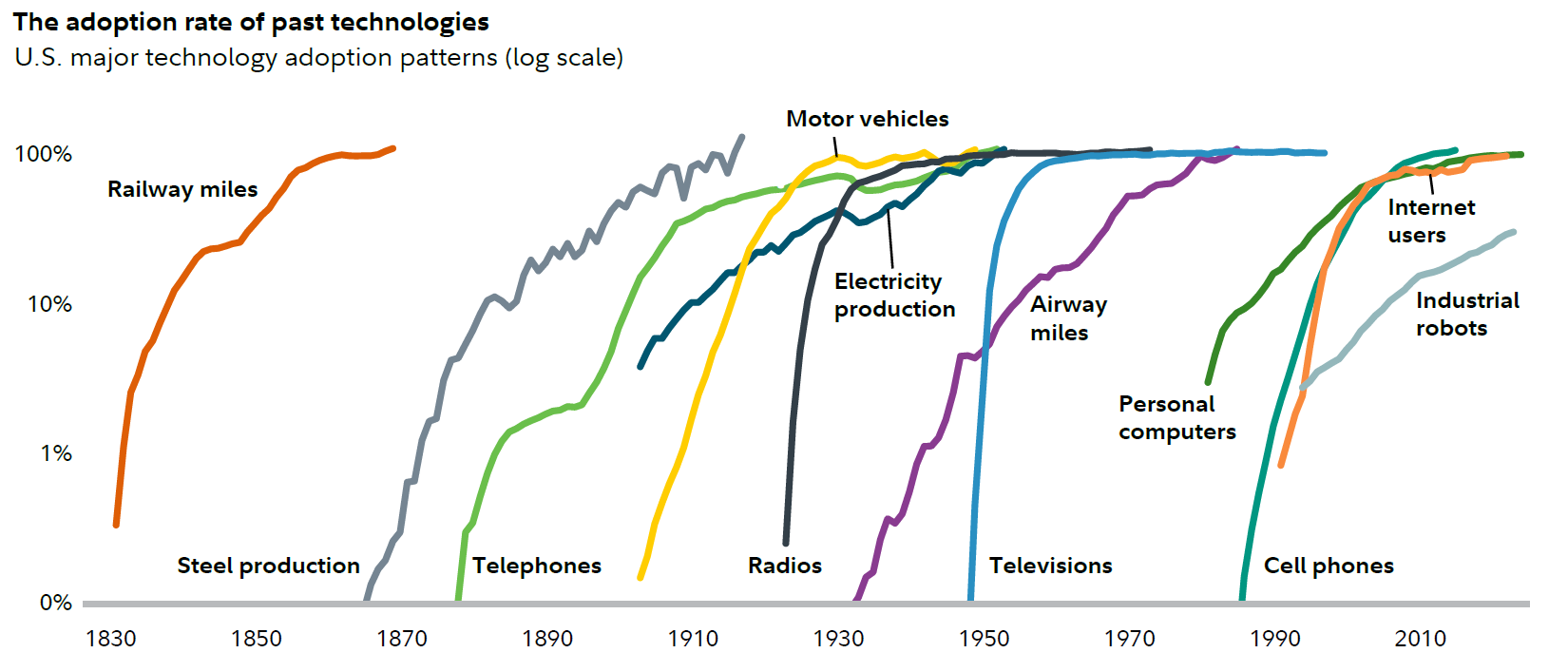

Tytell is the author of a recent Fidelity Institutional analysis that found that a major AI-driven acceleration in productivity in the next decade is unlikely. Sizable productivity gains are more likely to be seen when and if AI technologies approach 50% adoption, perhaps 10 to 15 years out from the present.

Using 3 approaches (aggregating experiences of past technologies, extrapolating technological adoption patterns by sector, and deriving estimates from capital spending), the analysis estimates a potential productivity boost of 0.2%–0.3% over the next decade, with gains of 0.5%–0.9% in the lead-up to widespread adoption.6

"Set against the 1.4% productivity rate of the last decade, these estimates are encouraging. Even a modest productivity boost would help counter demographic headwinds and support stronger economic growth," says Tytell. “However, with any new technology, there needs to be significant capital investment to get it going. There’s a very clear association between capital investment in the present and productivity in the future, and I don’t think we’ve seen enough of a pickup in the former to make us optimistic about the latter. It’s happening, but not yet in a big way.”

Much remains to be seen

It’s easy to get swept up in the excitement of a new technology, but patient analysis shows that a more measured approach may be the best way to take advantage of technological developments without getting too far ahead of things.

"My impression is that very often, as people, we tend to overstate short-term consequences and understate long-term consequences," says Tytell. “And I think AI is no exception to that. It is a very powerful new technology that has the potential to enhance productivity. But people may be expecting too much too soon. We may need to be a bit more patient. The potential benefits may be substantial, but they may also be further in the future than some anticipate.”