The number-1 question from our advisor clients early in 2026 is whether we think increased investment in artificial intelligence (AI) is creating a bubble for growth-oriented technology stocks either close to or on par with the dot-com craze.

Many technology executives believe AI will be transformative over time, result in productivity gains, and, by making labor and capital more efficient, lead to higher corporate profits, which we think is likely true.

The question, of course, is to what degree and how long it might take before we see meaningful incremental productivity gains. That's difficult for anyone to know.

Comparing the AI vs. dot-com eras

Investors who lived through the 1990s boom and bust likely have heard numerous enthusiastic messages from the tech industry, media, and growth-oriented investors that rhyme with the hype they heard about the transformational impact of dot-com companies nearly 30 years ago.

Let’s acknowledge a few things upfront:

- The promise of new generational technologies powered by AI have pushed stock valuations above historic norms (we’ll examine to what degree shortly).

- Capital expenditures on technology projects have risen rapidly, although the long-term aggregate return on investment remains unknown.

- We see some circular financing, meaning a percentage of AI investment is traveling in a loop among a small number of companies, making it harder to accurately measure the level of demand outside of those firms.

“All of this is true, but I don’t think investors seeking answers about AI’s future impacts can afford to be blindly skeptical about its long-term impact,” says Michael Scarsciotti, head of the investment specialists at Fidelity Investments. “It’s important to look past the easy, base-level parallels with the dot-com era if you want insights into the strength and duration of the AI investment trend.”

Why the end of the AI trend does not appear imminent

Spending on artificial intelligence has grown rapidly since the development of the first powerful neural network in 2012, similar to the way spending on computers increased following the advent of the microprocessor in 1973. Capital spending on each of these technologies increased rapidly for decades following their respective releases.

While the monetization of AI still lags investment, and more projects are being funded by debt (especially among private companies), the current spending trend on AI appears strong, evidenced by:

- Cloud services providers, such as Amazon Web Services, Microsoft, and Google, are expected to collectively ramp their AI spending in 2026.

- Sovereign governments have piled on with their own AI buildouts.

- Businesses in the banking, insurance, and other industries have gone beyond experimenting with AI and spending the money on platforms they plan to use longer term.

- Demand for semiconductors and related hardware used for AI projects remains robust.

Over time, some companies may begin to substitute incremental operating expenses for capital expenses, which could extend the AI spending trend.

The question is, how can we know the AI spending boom is unlikely to break down in the near term?

Keep in mind that, in past technology booms, including the dot-com era, the outsized corporate profit gains tended to last only a few years, as a large number of technology companies lacking profits, increased risk-taking, rising interest rates, and faltering investor sentiment brought the equity market down.

We think 5 indicators may offer directional insights into future AI-driven market and economic trends:

- The rate of aggregate earnings growth

- Aggregate earnings quality

- Valuations vs. history

- The affordability/sustainability of corporate capex spending, and

- The interest-rate cycle.

Below, we take a look at each in turn.

1. Earnings growth

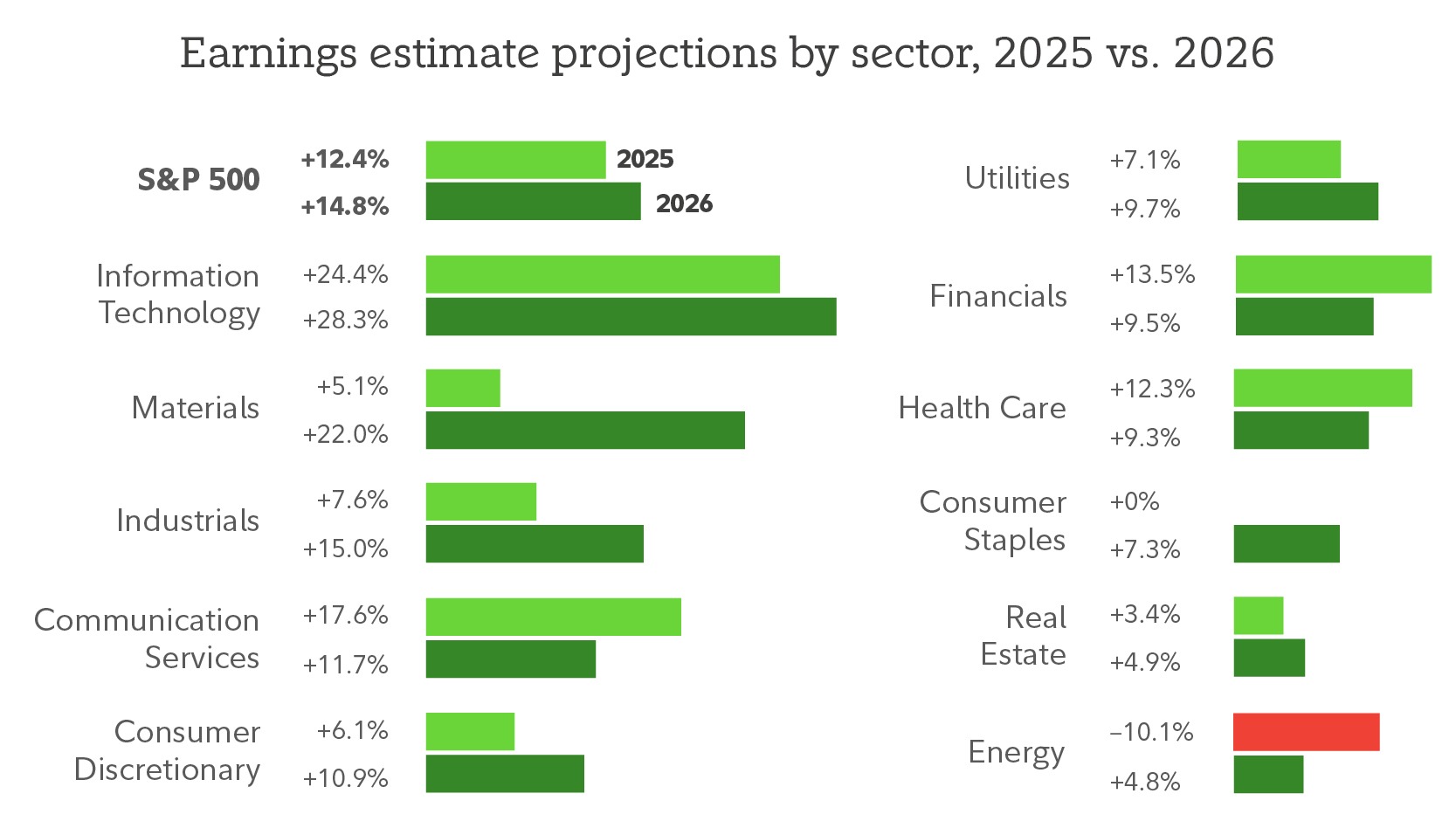

The S&P 500® Index appears on track for the 10th consecutive quarter of earnings growth, based on FactSet data, amid a continued US economic expansion. Analysts expect the third straight year of double-digit earnings acceleration in 2026, with contributions from each of the 11 sectors.

Importantly, revenue growth of about 8% in the third quarter, the highest rate since the third quarter of 2022, backs the strong earnings trend. For calendar year 2026, the revenue growth projection of 7.2% remains comfortably above the 10-year average annual revenue growth rate of 5.3%.

As the chart below shows, analysts expect year-over-year earnings growth to accelerate in 2026.

Looking ahead, we want to keep seeing above-average earnings growth in the aggregate, profits backed by strong revenue growth, and an above-average number and a wide range of companies topping expectations in a mix of industries.

Also, we often analyze the “Magnificent 7” stocks (Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, NVIDIA, Meta, and Broadcom1 ) individually and together, since this group of stocks composes more than a third of the S&P 500’s market capitalization. In the third quarter of 2025, these companies reported the lowest earnings growth since early 2023, although we believe one-time issues influenced this result. Overall, we see potential for higher earnings growth for these companies in 2026.

While both the shorter- and longer-term earnings trends appear robust, we’re always watching for any potential breakdown in aggregate earnings growth or a below-average percentage of companies topping expectations. In historically expensive stock markets (like the present), negative earnings surprises have led to more market downside than at other historical points.

2. Earnings quality

As of late 2025, we believe earnings quality for companies in the S&P 500 remains healthy. As always, we continue to monitor various earnings quality measures going forward. As investors learned in 1999, earnings can be “fake” at or near market highs.

Here are some of the measures we are watching:

Cash flow vs. earnings: It’s a positive sign if the cash flows that companies report exceed their reported net income. Based on aggregate net income of S&P 500 companies minus their free cash flows—all divided by total operating assets—this measure of earnings quality has strengthened vs. recent years and has not recently shown signs of weakness.

Aggregate margins: The S&P 500’s net profit margin of 13% in the third quarter (the latest reported) topped its 5-year average (about 12%), driven partly by information and utilities firms, each of which have benefited from AI spending. The estimated profit margin for 2026 recently stood at about 13.9%.

Non-adjusted earnings: The earnings companies in the S&P 500 report often include adjusted per-share figures that are not in line with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). Therefore, we track the aggregate trend of GAAP earnings per share, which has increased each year since 2020 and continues to look healthy.

Aggregate earnings restatements: Investors in the dot-com era may recall the many accounting scandals and the frequent restatements of previously reported company earnings that lasted through the mid-2000s. While we did see an increase in earnings restatements in 2021, partly driven by accounting issues for special purpose acquisition companies, the long-term trend has been toward fewer restatements—especially for larger firms. Since 2021, the restatements trend has continued to decline.

3. Valuations vs. history

At the end of last year, the S&P 500 traded at about 22.3 times forward earnings, which is above its 10-year average of about 18.7 times. Also as of December 2025, the S&P 500 traded below the aggregate dot-com era valuations, but only about 10% below the July 1999 peak of 24.4 times.

Information technology, while offering faster aggregate growth, remains the most expensive of the 11 sectors (about 27 times as of December 2025). This is still below the sector multiple of more than 45 times earnings in early 2000.

Let’s also look at the market’s most influential stocks both today and in the dot-com period. As of December 2025, the top 7 stocks by market capitalization, “the Magnificent 7,” traded at about 28 times forward earnings.

That’s less than half the roughly 66 times forward earnings we calculated for the 7 largest stocks by market cap in 1999.

| Top 7 stock valuation comparison, dot-com vs. AI eras | |

|---|---|

| 1999 price-to-earnings peaks | December 2025 price-to-earnings peaks |

Average: 65.6 |

Average: 28 |

Source: FactSet and Fidelity Investments, as of December 31, 2025.

4. Capex: Can companies afford it?

The trend for capital spending on AI-related projects continues to move up and to the right, driven by:

- Data center projects

- Electricity projects to power data centers

- The development of new and updated large language models

- AI-driven workflow automation projects that seek to automate supply chain, finance, and human resources tasks

- “AI agents,” or autonomous software systems that generate code, provide customer service, and analyze data to help solve complex problems

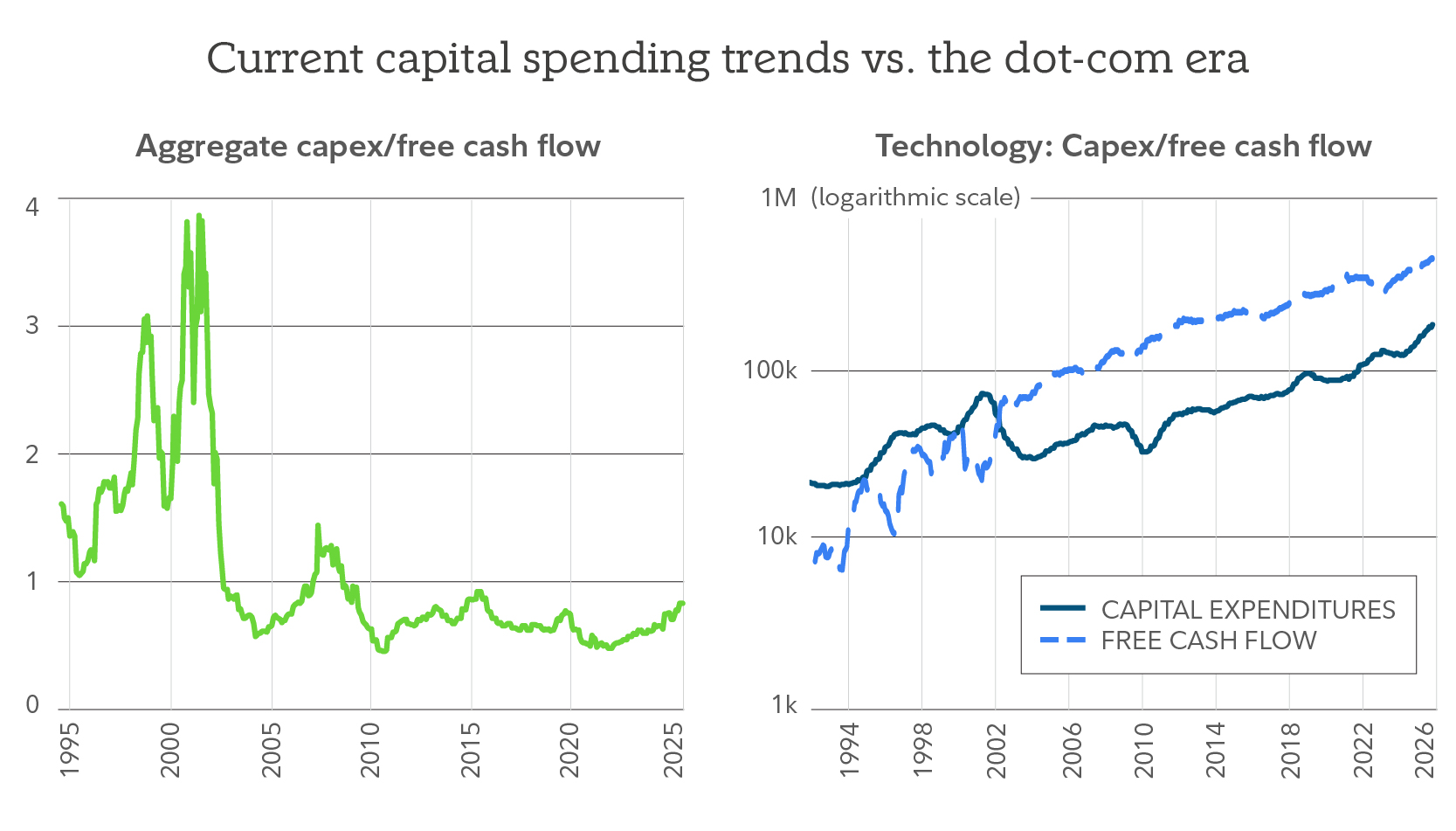

In 2024, the 5 main hyperscalers—Google, Microsoft, Amazon, Meta, and Oracle—had $241 billion in capital expenditures. Capex spending by these companies is expected to rise to half a trillion dollars in 2026. Some of the news headlines about increased AI spending make comparisons vs. the excess years of the late 1990s.

What’s different today is that companies largely are spending what they earn on technology projects, not what they borrow.

The chart below to the left shows the capex-to-free-cash-flow trend for the broad Russell 3000 index. This ratio peaked at nearly 4 times free cash flow in 2000, but it is currently below 1 (with 1 and below reflecting aggregate spending from earnings, rather than debt). It does not appear to reflect speculative excess.

The chart below to the right breaks out the long-term capex-to-free-cash-flow trend for the information technology sector on a logarithmic scale. Before the dot-com bubble burst, technology companies were spending more than the cash they generated for nearly a decade. Today, it’s the opposite trend.

5. The rate cycle and why it matters

Lastly, the connection between Fed hiking cycles and market bubbles has often followed a predictable pattern: Bubbles have burst following extended periods of excess liquidity (most often after an era of low rates). The liquidity excesses eventually reached a breaking point after the Fed then raised rates to combat economic instability, inflation, inefficient uses of capital, widespread risk-taking, or a combination thereof.

The table below notes past market bubble periods and their respective peak-to-trough market declines. Notably, each occurred before or during the start of increased interest rates. As of late 2025, the Fed remains in a period of decreased policy rates.

Lower rates tend to make it cheaper for both consumers and businesses to borrow, which has led to past surges in spending and increased asset prices. However, in past bubbles, the “burst” happened when the Fed had to respond by raising rates.

This may be something to monitor going forward, but we believe rate hikes do not appear to be a concern at present.

| Asset bubbles have tended to burst after the start of Fed hiking cycles | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period | Start of tightening | Peak rate before burst | Total increase in rates | Peak-to-trough market decline |

| Great Depression | Early 1928 | 6.00% | +250 basis points (bps) | Dow Jones Industrial Average −89% |

| Dot-com bubble | June 1999 | 6.50% | +175 bps | Nasdaq Composite −78% |

| Housing bubble | June 2004 | 5.25% | +425 bps | S&P 500 −57% |

| Period | Start of loosening | Current rate level | Total decrease in rates | Market performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current cycle (2024–early 2026) | Sept. 2024 | 3.75% | −175 bps | S&P 500 +24% |

Peak-to-trough market declines calculated using different indexes to attempt to reflect the most influential market measure for each respective era. Source: FactSet and Fidelity Investments, as of December 31, 2025.

Also, we are not seeing any of the following potential warnings as of early 2026 that might alert us to a potential AI bubble:

- Shrinking free cash flows amid aggressive spending on AI infrastructure

- Increased cross-holding of US stocks on corporate balance sheets

- Deteriorating leverage ratios amid a debt-fueled AI expansion

- Compression of price-earnings multiples for AI stocks due to electric power and computing bottlenecks that stifle growth

- Wider credit spreads

Conclusion

The impact of AI spending on the US economy is real. It’s hardly the sole driver of growth, but we believe it is providing a meaningful tailwind. Meanwhile, the growth of AI stocks has supported wealth effects (a K-shaped economy, in which market gains bolster the spending of wealthier households, and thus, the overall economy).

While we continue to monitor the health of AI trends, we think it remains strong and, in some corners of the market, underappreciated. For example, we see opportunities among professional services companies, industrials firms, health care, and utility companies. Similarly, we see potential among AI investments outside the US, including semiconductor firms, cloud application providers, companies working to power data centers, and businesses that own unique data sets.

In our view, AI remains in an early economic development stage. It’s likely to experience growing pains, and it may take more time before the rate of revenue and earnings from AI begins to match the rate of spending.

Risks associated with AI include its potential investment overexposure. Like all thematic investments, it’s important to balance AI-related holdings with a healthy mix of other equities, including other large caps, international equities, mid caps, and select value stocks. We believe balanced exposure to fixed income also is important, and that select alternative investments could also add value over the long term.