If you have a mortgage or car loan, you may have heard the term "amortization." But the term applies to more than just loans, and even with loans, you might not understand exactly what amortization really means. So here's an amortization definition, plus why it matters.

What is amortization?

Amortization is the regular, fixed reduction in value of something over time. In finance, amortization commonly comes up in 2 main ways: with debt and with assets. With debt, you might pay off your mortgages, auto, personal, student, or home equity loans in predictable, reoccurring installments. For intangible assets with a set useful period, like a patent with an expiration date, businesses may account for that cost in regular expenses spread out over time, rather than all up front. (Generally, tangible assets' reduction of value is called depreciation rather than amortization.) For this article, we'll primarily be discussing amortizing loans rather than assets, though we'll briefly touch on how all of this works for intangible assets.

How does amortization work for a loan?

In an amortizing loan, you pay the same amount according to a payment schedule. For example, mortgage payments are usually made monthly over 15 or 30 years. Every payment goes toward 2 costs: your principal, aka the amount you borrowed, and interest, which is what the lender charges you for borrowing that money. In the beginning, more of the payment is dedicated to interest. Because interest is charged on the balance, as you pay down the principal, there's less interest left to pay, and more of each subsequent payment goes toward the principal.

The more years there are in a loan term, the lower the regular payments are because they're spread out over a longer duration. The other side to longer amortizing loan terms: You end up paying more in interest because interest has more time to accrue.

This is different from non-amortizing loans, like credit cards, home equity lines of credit (HELOCs), securities-backed lines of credit (SBLOCs), and balloon-payment loans (a loan that charges lower payments until the end, when it requires a bigger payment, or the "balloon"). Their principals' value doesn't predictably decrease throughout the life of the loan. For example, let's say you have a $5,000 balance on your credit card that you plan to pay down. You could make the minimum $1,000 payment one month, pay $2,500 the next month, and pay another $1,500 the next month. Your balance dwindles based on what you decide to pay each month and on the accrued interest, not on a predictable schedule with fixed payments.

What is an amortization schedule?

An amortization schedule, in the case of loans, is a table of regular payments applied to a balance until the loan is paid off. It usually includes:

- the total loan amount

- the regular, fixed payment

- the interest rate

- how much of each payment is applied to interest and principal

- the remaining loan balance after each payment is applied

- the loan term

Intangible assets, such as patents, trademarks, and copyrights, have amortization schedules too, tracking the declining value over time.

Amortization example

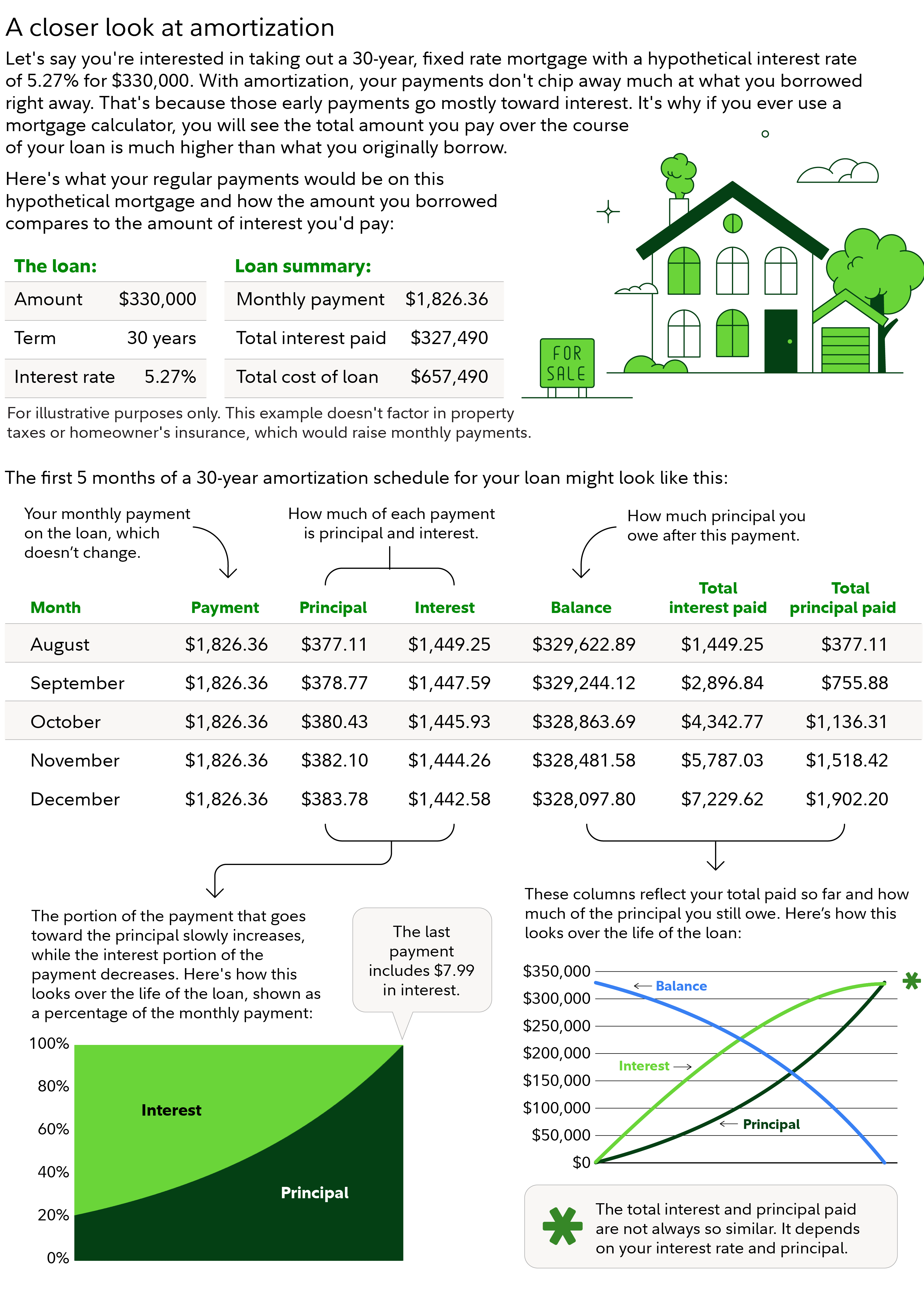

To help you better understand amortization, check out this quick example about how it could play out for a mortgage, though this breakdown could apply to other kinds of amortizing loans too. This hypothetical example illustrates how the percentage of your mortgage payment going to interest (versus paying off your principal) varies over time.

As these hypothetical charts show, the monthly payment in this amortization schedule stays the same throughout the life of the loan because the interest rate is fixed. Still, the portion of that $1,826.36 devoted to interest and principal, respectively, changes with each monthly payment. The bulk of early payments goes toward interest while the bulk of later payments goes toward the principal. Even the final payment after 30 years includes $7.99 in interest.

How is an amortization schedule calculated?

An amortization schedule is calculated using the following 2 formulas for all monthly payments. You can plug in the numbers a potential lender may provide you, based on the amount you would like to borrow.

First, you would calculate the portion of the next payment that goes toward interest with this formula: (Remaining loan balance × interest rate)/12 months = interest for the next monthly payment

Then, to see how much of the next monthly payment goes toward the principal, you could subtract the interest, found using the first formula, from the fixed monthly payment. Or you could use the following formula:

Monthly payment – (remaining loan balance × (interest rate/12 months)) = principal for the next monthly payment

Using the same 30-year $330,000 mortgage with a 5.27% fixed interest rate example from earlier, here's what the formulas would be for calculating the portion of the first monthly payment that gets applied to interest and principal:

Interest formula:

($330,000 × 0.0527)/12 = $1,449.25, the portion of the $1,826.36 payment that goes toward interest for payment 1.

Principal formula:

$1,826.36 – ($330,000 × (0.0527/12 months)) = $377.11

For the first payment on that 30-year mortgage, that would be:

$1,826.36 – $1,449.25 = $377.11

To calculate how your payment is apportioned for payments 2 and beyond, subtract previously applied payments to the principal from the starting principal to get the remaining balance.

For instance, sticking with the mortgage example, payment 2's interest formula would be:

($330,000, the starting principal – $377.11, the portion of the first payment applied to the principal) × 0.0527, the interest rate)/12 months = $1,447.59, the portion of the second payment that will apply to interest

Since it would take a lot of math to do this for all 30 years of payments, you could instead look for online amortization calculators or even use tools built into spreadsheet software.

Why is amortization important?

Amortization is important because it can help borrowers understand how much borrowing money to fund their purchase would cost in total, including interest, if they make the expected monthly payments. Using the earlier example, if a borrower takes out a hypothetical 30-year, $330,000 loan with a 5.27% interest rate, over the 30 years, the borrower would ultimately pay $657,490 ($330,000 in principal plus $327,490 in interest) to own the home.

But you can check how paying more frequently than your schedule affects your payback timeline by plugging in numbers in online amortization/mortgage calculators. For example, by splitting your monthly payment into ones made every other week instead, you'd end up paying the equivalent of one extra monthly payment per year, thereby reducing the interest you owe over the life of the loan. Other ways to help reduce the total cost of your mortgage include making additional payments on top of the existing monthly payment, refinancing to a lower interest rate, or recasting, which is putting a lump sum toward your balance to reduce monthly payments and the total interest you’d pay over time.

Amortizing intangible assets

Amortizing intangible assets works differently than loan amortization. A company usually divides the cost of the asset by the number of years of its useful life. For example, a trademark that costs $15,000 and is good for 15 years would be amortized as $1,000 per year over 15 years. This kind of amortization is important because the company can deduct a $1,000 expense each year for 15 years on its taxes. This could help the company manage costs, align expenses with revenues (so profits aren't distorted by a huge one-time expense), and save on taxes.